Vocal Anatomy 101

This is Your Voice

Sound doesn’t just happen; there’s a scientific explanation for exactly how we speak and sing!

First, we breathe in.

Air then moves up from your lungs into your trachea (windpipe).

Before it hits your mouth, and then enters the space in front of you, it moves through your larynx (voice box). The larynx moves up and down and can sit lower, at a mid/ netural place, or high; this creates different vocal timbres (i.e. a more ‘classical’ sound uses a lower larynx; pop music sits in the mid-range; and a brighter ‘musical theatre’ or ‘mickey mouse’ sound uses a high larynx)

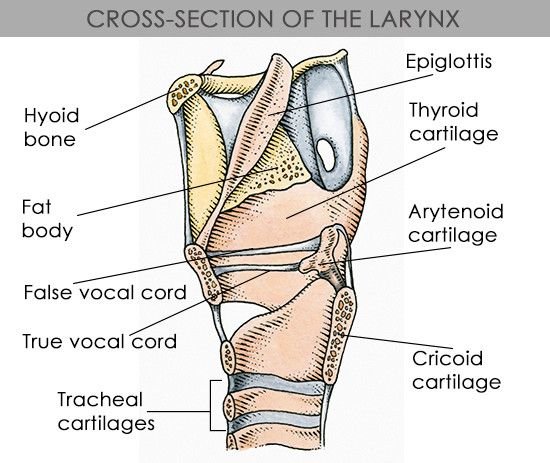

Your larynx contains two pieces of tissue called your vocal folds (sometimes called vocal cords); the air creates a difference in pressure above and below the folds, which then vibrate together incredibly fast to make sound (60-2000 times per second); this is called phonation. We can use the muscles in our torso to increase the pressure with faster or slower airflow and influence the volume of our sound.

The muscles and cartilages around your vocal folds also cause them to lengthen and contract - think of a rubber band stretching and relaxing! This causes the folds to vibrate slightly faster or slower, which changes the pitch of your sound. There is a thicker and thinner part to the vocal folds, which is where the idea of ‘chest voice’ and ‘head voice’ comes from; we tend to use the thicker part in our ordinary speech and loud yells and the thinner part for high pitched speech like cooing at a baby; however, we can use either part at any pitch with practice! There are also other cartilages which we can engage or ‘tilt’ in different ways to allow for different qualities; this is where we can form vibrato and a belt. Just above the vocal folds are bits of tissue which we can squeeze together or open up wide; these false vocal folds can allow for a sound that is a bit more pressed and rock-heavy or very clear and bell-like like a princess.

The vibrations from your larynx next make their way up past the epiglottis; this is a small piece of tissue that covers either the trachea or esophagus depending on whether you are swallowing or speaking. It is covering the esophagus when we sing and is open to the trachea, allowing air through your pharynx (the back of your mouth and nose). The back of the tongue can also narrow towards the back of the mouth at a lower or higher part; this narrowing can make the voice sound more resonant (think kermit the frog for an extreme example), or bright and twangy (think a twangy, bluesy country singer or a whiny, bratty child asking for a toy).

Your soft palate determines how much air enters into both your oral cavity and nasal cavity (mouth and nose) . When the palate is low and close to the back part of the tongue, more air enters the nose; when the palate is high and far from the back of the tongue, it begins to close off the path to your nose and more air enters the mouth.

The sound is amplified in the oral cavities and nasal cavities, as well as secondarily through the sinus cavities; this is another way we influence volume.

The tip of the tongue, lips, and jaw shape the different vowels that we can make; in English, the basic vowels are A, E, I, O, U (each of these, and different combinations of them, can make different sounds - for example, the difference between “cat” and “caught”). Your tongue is much bigger than many people believe; see the picture to see just how much space it takes up! The tongue is also responsible for articulating the consonants that we use (all letters except the vowels). We can also use muscles in our torso and cheeks to anchor things in place and give us detailed control over all of the components we have now aligned however we have chosen.

Finally, having shaped the air however you want to, it makes its way out of your mouth and nostrils into the space in front of you to create a huge variety of sounds!